By Manisha Vaze, Director, NFG Funders for a Just Economy

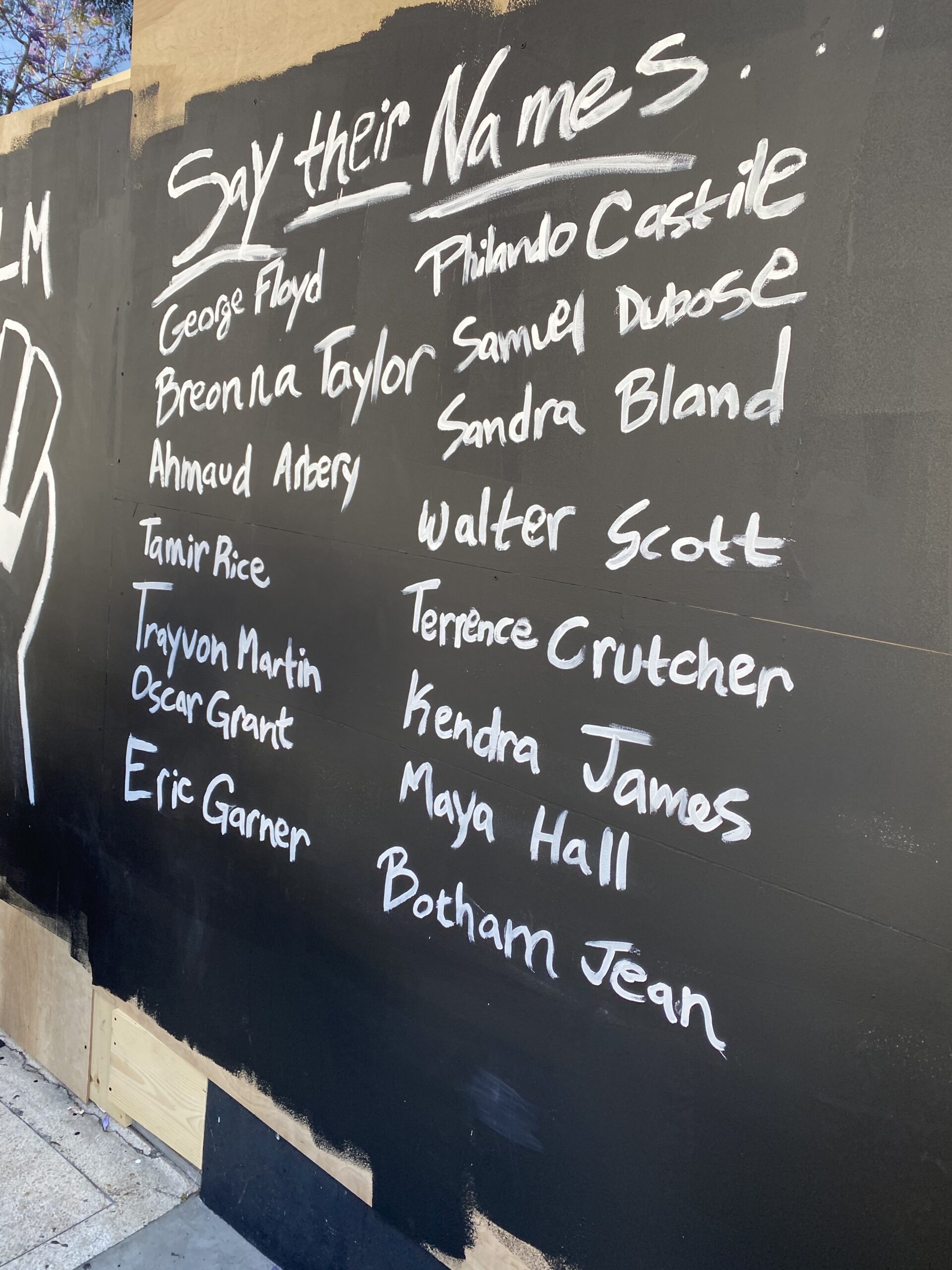

As we close this year, it’s probably safe to assume that you, like me, are emotionally and physically exhausted. The never-ending tragedy of this year’s global pandemic, the job loss, the deep inequality of the economic and health systems, and the new exposure for many Americans to systemic racial injustice, racial terror, and state violence overlayed our own personal losses and struggles. For me, while my partner and I were lucky enough to keep our jobs, it included family and friends who had COVID-19, a family member killed by the police, and much time away from our loved ones. I’m really ready for a winter break.

Prior to joining NFG, I organized alongside immigrant families facing deportation in New York City and with chronically un- and underemployed people in South Los Angeles. My political education is rooted in the organizing I was involved in as a student in the early 2000s, and movement responses to 9/11 shaped my experiences of centering Black and Indigenous communities in our fight against surveillance and violence against Arab, South Asian, and Muslim communities. We organized to address the continued consolidation of corporate power, surveillance technology and data control, as well as new austerity policies, unimaginable (at the time) job loss. We confronted radically accelerated separation of families, detention, and deportation of migrants by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and hand-in-hand with police. I learned to listen to people, dream big, demand what we actually need (not just what is winnable), and build towards that interlocking vision of economic and social justice through strategic and incremental wins and constantly evolving tactics.

Today, as the new US federal administration begins to take shape, some may be content with a collective sigh of relief. However, the organizer in me is asking you to stay vigilant and move resources to where movements are directing us: to organizing, power building, and movements calling to defund the police as a pathway to community and worker justice. We have an enormous opportunity in philanthropy to truly support, through solidarity and resources, the visionary movements that are building power for systemic change. Movement organizers have made significant gains in 2020. The cultural shifts we’ve experienced as a result have unprecedented numbers of people calling for abolition of the police and ICE, supporting unions in new industries, and shifting and expanding public budgets. Organizations have built and formed stronger coalitions, multi-racial, multi-gender, and multi-sectoral movements. And, importantly for our sector, the highly-visible organizing power of community members and workers has moved foundations to understand how philanthropy has supported extreme wealth accumulation and is entrenched in the perpetuation of racial capitalism and heteropatriarchy. Collectively, this has resulted in foundations increasing their investment in organizing and advocacy efforts toward economic and racial justice.

To some vocal pundits and media, defunding the police sounds like a new concept born out of the George Floyd uprisings, but it is a decades-old call to action, voiced by Black feminist leaders and those most impacted by police violence. Visionary movements that have been calling for defunding the police see how this strategy releases revenue that can be invested into infrastructure, social protections, housing, worker protections, and other community needs. Upending the power of police unions, not just “reforming” them, will allow more opportunities for strategic campaigns that realign public budgets and real community safety to meet the community’s needs and the goals of philanthropy’s investments in economic justice and equity.

Furthermore, defunding the police, ICE and violent surveillance forces offers an opportunity to align with workers expanding the labor movement. Police unions have since their inception had contentious relationships to workers calling for better working conditions, safety nets, and social protections. The expansion of policing in the late 19th century was precisely to bust labor organizing during work stoppages and strikes. In the last decades, we have seen countless examples of employers using immigration (now ICE) raids to threaten workers who attempt to organize. The labor movement has long recognized the antagonistic role police played on the picket line, and chose not to build with their unions. And the reality is that while some police unions are part of these institutional labor structures, most police associations are not – maintaining a business association 501(c)(6) status instead of a tradition labor union status or 501(c)(5).

If we’re serious about worker power and contesting for governing power in the US it’s important to recognize how the police and carceral systems hamstring the movement’s ability to make strategic and progressive policy gains. Their outsized power influences public budgets, dictates narratives about community safety, and render them immune to scrutiny and accountability. All of this leaves community members and workers who organize to increase funding for public schools, transportation, job quality, healthcare and other needs, fighting for scraps. The good news is, the decision to prioritize criminalization over community care and economic development is a relatively new one, borne of decades interlocking efforts to shift public narrative, policy and power. This orientation is by no means inevitable, and can be countered by a concerted, long-term power-building effort that includes partnership from philanthropy.

At NFG’s Funders for a Just Economy, I am privileged to work with funders who inspire me to think differently about philanthropic work and grant making, and have led efforts in our network to understand power, how to shift it to transform communities, and learn how racial capitalism undergirds our economic system and impacts our work in philanthropy. Most recently, FJE interviewed Jidan Terry-Koon, FJE Coordinating Committee member and Director of People pathways at the San Francisco Foundation who shared that if funders truly centered the most marginalized, especially Black and Indigenous workers in their economic justice grantmaking, they would understand the connection between building the power of all workers and shifting funds away from the police and carceral systems. FJE members have also formed deeper partnerships with Funders for Justice (FFJ), now an independent organization, to support movements to divest from the police and the carceral system and invest in community safety, housing, and other public investments.

We need to open ourselves up to a longer arc of change. The leadership of worker movements and coalitions inspires me to envision where we could be in the next twenty years. Learning from FJE’s programming, I know we can move more money for justice. Movement leaders have called for these changes in philanthropy before, and I’m recommending them again. Philanthropy must mobilize to:

- Make multi-year, general support investments and grants in base building and organizing.

- Collaborate with other funders to ensure that we’re building community power and supporting local and regional ecosystems.

- Influence funders to deeply fund organizing efforts that build community and worker power, and especially worker organizations that build power to make impact (in addition to and) beyond their workplaces to support the common good.

- Fund groups that are building a new transformative economy through alternative wealth building including cooperative models and other small business development.

- Advocate to increase your yearly grantmaking, and your institutions assets, resources, and influence to support power building and organizing.

- Learn about your institution’s finances and make adjustments to divest from the criminal and carceral systems and invest in non-extractive industries.

- Utilize your relationships with allies in organized labor to fund collaborative efforts that build power locally and shift state and federal policy.

- Continue your own education and build consciousness amongst your colleagues about the history of the mass accumulation of wealth in philanthropy rom centuries of corporations extracting wealth from enslaved people, people who are incarcerated, workers who are not paid living wages and without any job security or social protections, and a rigged tax system benefiting the wealthy.

We must support the movement’s call to defund the police and abolishing ICE as a pathway to building worker power. This year showed us that, if forced to, funders can move money quickly – let’s not wait until we’re forced to again. As funders of the worker justice movement, we can no longer stay out of this fight. As I count the days until the end of the year, I will be taking time to rest, heal, and get ready. We have much more work to do.

To learn more about how philanthropy can move resources to movement groups calling to defund the police and reimagine community safety, make sure to read and share Funders for Justice’s Divest/Invest online toolkit for funders. To continue to support and build community and worker power and racial, gender, economic and climate justice, stay connected to Rob and me to help advance NFG’s Funders for a Just Economy program.

Photos by Manisha Vaze from Black Lives Matter/Defund the Police protests in Los Angeles, California in Summer 2020.