Introduction

Principles and practices that center community accountability should be part of philanthropy’s core purpose. Considering the history of philanthropy [1], we know that philanthropy does not own the resources it contains, and we must fully support community-identified priorities and community-led change. This resource was adapted from content from an NFG hosted webinar titled “Do Better: Grantmaking Practices Toward Community Accountability” to share our learnings and reflections.

Philanthropy can be organized to become stewards of resources that should be utilized for the public good, rather than hoarders for gatekeepers of wealth. NFG organizes with funders towards the goal of liberated philanthropic assets so that BIPOC communities and low-income communities have power to self-determine. The task we are charged with is how to support these community organizations, build collective power, and bolster the connective tissue across different movement spaces. The community organizing ecosystem can be siloed oftentimes because of segregated funding lines, both public and private. In exploring ways for philanthropy to do better, there is much to learn from increasing values-based practice, grantmaking, and funder organizing.

Values-Based Practice

It is imperative to routinely ask ourselves what our values are, and assess how they guide, anchor, and influence our practice. Philanthropy must find ways to nurture and strengthen the conditions necessary to build decision-making power for historically marginalized people and BIPOC communities, and to shift where, to whom, and how philanthropy is providing support. This starts with our values, which will determine how we are ceding power and showing up in true partnership with community organizations and social movements.

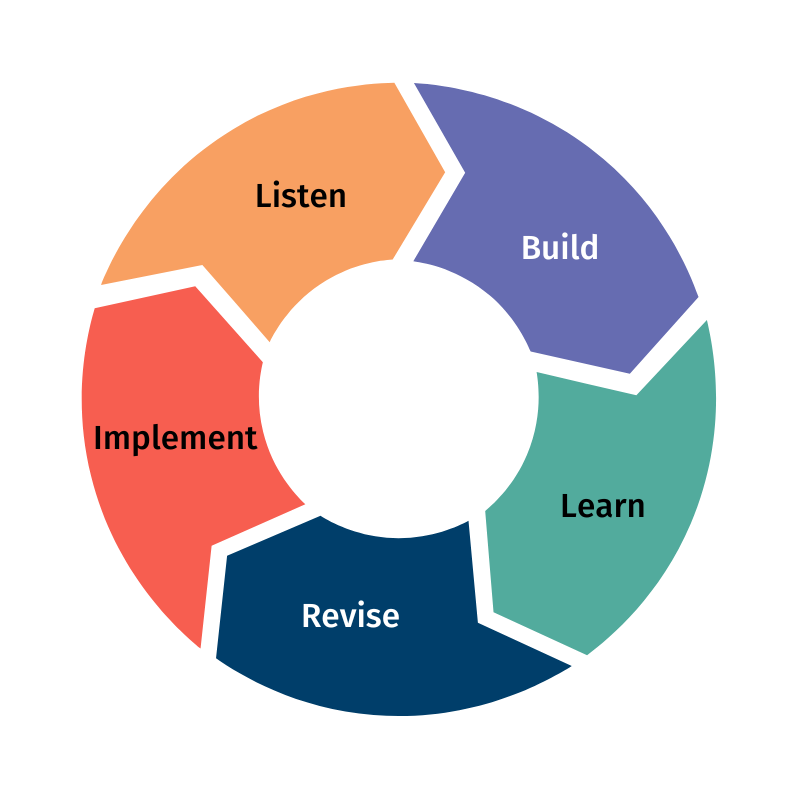

To begin this reflection, ask yourself who are you accountable to. Be honest about the list, and who is at the top. How do you manage and prioritize? Who do you ask first - whether it’s about developing strategy, resources, or practice. Be mindful of where community organizations and grantees are in that reflection, and where coordination and consultation with them can be more meaningfully incorporated. In order to truly be responsive, we must engage in an iterative process and take the time necessary to learn, practice, and adjust.

Grantmaking

To move in partnership and in a way that centers community, we must shift from transactional grantmaking to one of partnership, especially partnership that aligns a shared vision with grantee partners and practices that reflect it. We're not just asking what organizers hope to accomplish or if the the work is possible. But rather, we must ask what is needed to accomplish this work, and then take it upon ourselves to figure out how to make that happen.

In line with this thinking, we must also turn the mirror to ourselves and determine if what we are asking of grantees is really necessary. How can we streamline applications, reporting, and evaluation in ways that are mindful of grantees’ time and deliver only what we really need? For example, removing arbitrary “required” deadlines and documentation.

Additionally, how are we generating a more democratized, participatory decision-making process on where resources go? This can look like grant panels that involve grantees and community, and paying folks for their time to offer expertise and partnership.

How do we define community? Organizations that are made up of members from the communities in which they work that are engaged in working on improving or dismantling systems of oppression. Movements are the ecosystem of grassroots communities that have direct accountability and are engaged in feedback loop with frontline communities themselves.

Funder Organizing

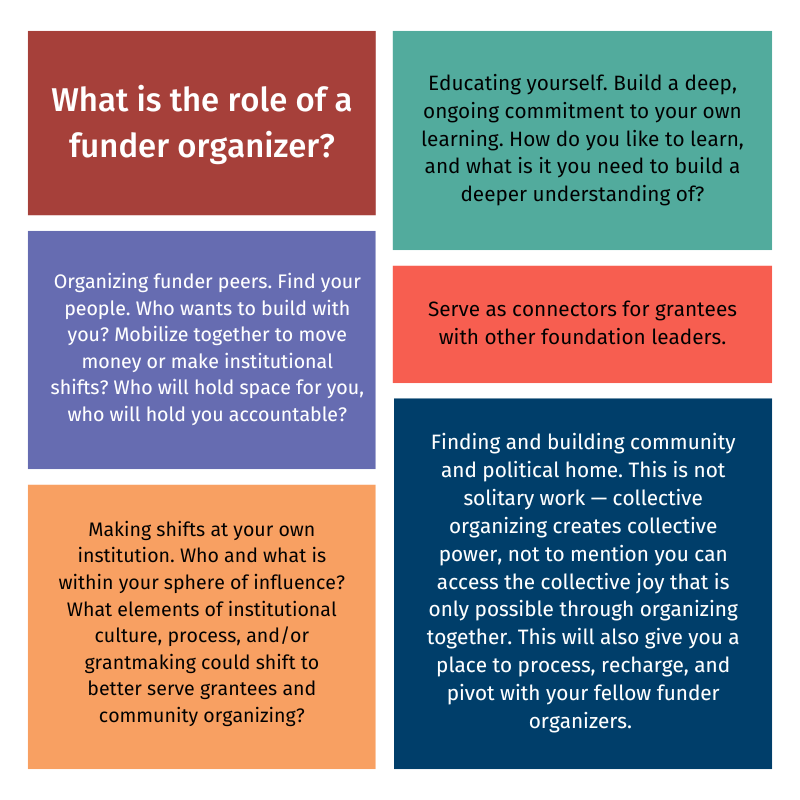

For grantmakers seeking to do better in their efforts to support social movements, it is also imperative to organize colleagues within individual institutions and across philanthropy as well. Kataly Foundation defines funder organizing as moving an individual donor or institutional funder from a specific stance or orientation on an issue into action through deep relationship building and

politicization [3].

What, then, does it mean and look like to be a funder organizer? At NFG, we propose that a funder organizer is someone who is a movement advocate, connector, and mobilizer in a foundation. They organize their grantmaking institution to shift philanthropic resources to movement, including advocating for grantees to receive funds and in more flexible and generous ways. They organize

their peers by building relationships, championing spaces for strategy and accountability, and inviting them to be in practice of their values. They actively try to dismantle philanthropic culture and practices in order to shift power equations needed to achieve our goals.

It is on us to organize as philanthropy and to be responsive to the community. As funders who seek to organize ourselves, our peers, and institutions, we must also develop a relational and values-based practice. To be a funder organizer, we must know who our co-conspirators will be in principled struggle with us around our values, stay accountable to those values, and deepen and sharpen them as necessary. Who do you give and receive feedback with? What are your anchors and buoys? This practice of defining values and moving in ways that align with them will transform you, your work culture, and your grantmaking.